Low-Carb Diets and Cholesterol: The Surprising Truth About Heart Risk

For decades, dietary fat and cholesterol were vilified as the root causes of heart disease. The prevailing wisdom was simple: eat less fat, especially saturated fat, and keep your cholesterol low—especially your LDL (low-density lipoprotein), often dubbed the “bad” cholesterol.

But emerging research over the past two decades has completely reshaped our understanding of heart health, cholesterol, and the role of diet. In particular, low-carb and ketogenic diets—once feared for their fat content—are now scientifically recognized for their ability to improve key markers of cardiovascular risk, including triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, inflammation, and even blood pressure.

This article aims to debunk the fear around low-carb diets and heart disease—and show why, for many people, cutting carbs may actually support heart health rather than harm it.

Rethinking Cholesterol: LDL Isn’t the Whole Story

The traditional metric for assessing heart disease risk has long been LDL-C (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol). However, research now shows that LDL particle size and number (LDL-P), not just LDL-C, are more predictive of risk[1].

Here’s the nuance:

- Small, dense LDL particles are more likely to penetrate arterial walls and become oxidized, contributing to plaque buildup.

- Large, buoyant LDL particles are much less atherogenic.

- Low-carb diets often increase LDL particle size—which is actually a favorable shift[2].

Further, LDL alone is a poor standalone predictor of cardiovascular events. More comprehensive risk markers include:

- Triglyceride-to-HDL ratio

- ApoB levels

- Lp(a)

- High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP)

- Coronary artery calcium (CAC) score

The Triglyceride-HDL Connection: A Powerful Predictor

One of the most consistent findings across low-carb studies is a dramatic drop in triglycerides and a significant rise in HDL cholesterol—both strong indicators of cardiovascular health.

- Triglycerides often drop by 30–50% on keto and low-carb diets[3]

- HDL (“good” cholesterol) increases by 10–20% or more[4]

- The Triglyceride-to-HDL ratio, a strong predictor of insulin resistance and heart risk, improves significantly[5]

These shifts are not only consistent but occur rapidly—within weeks of starting a well-formulated low-carb diet.

Inflammation: The True Culprit in Heart Disease?

Increasingly, scientists recognize that chronic inflammation, not cholesterol alone, plays a key role in the development of heart disease[6].

Markers of inflammation (like hs-CRP) often decrease on low-carb diets, especially when excess glucose, insulin, and visceral fat are reduced[7].

Low-carb diets also lower levels of:

- Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

- Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)

- Oxidized LDL (oxLDL)[8]

These anti-inflammatory benefits are crucial in preventing atherosclerosis, the root of most heart attacks and strokes.

Clinical Trials: What the Science Actually Shows

The landmark Virta Health study followed individuals with type 2 diabetes on a well-formulated ketogenic diet for 2 years:

- Triglycerides dropped by 24%

- HDL increased by 18%

- LDL-C increased slightly, but LDL particle size improved

- hs-CRP (inflammation marker) decreased by 39%

- Blood pressure dropped significantly[9]

Importantly, cardiovascular risk scores improved even though LDL went up slightly in some participants.

A 2020 meta-analysis of low-carb diets found:

- Significant reductions in body weight, blood pressure, and triglycerides

- Increases in HDL

- Neutral effects on total cholesterol and LDL-C[10]

And a 2022 study concluded:

“Carbohydrate restriction has a favorable impact on atherogenic dyslipidemia and other markers of cardiovascular risk—particularly in people with insulin resistance.”[11]

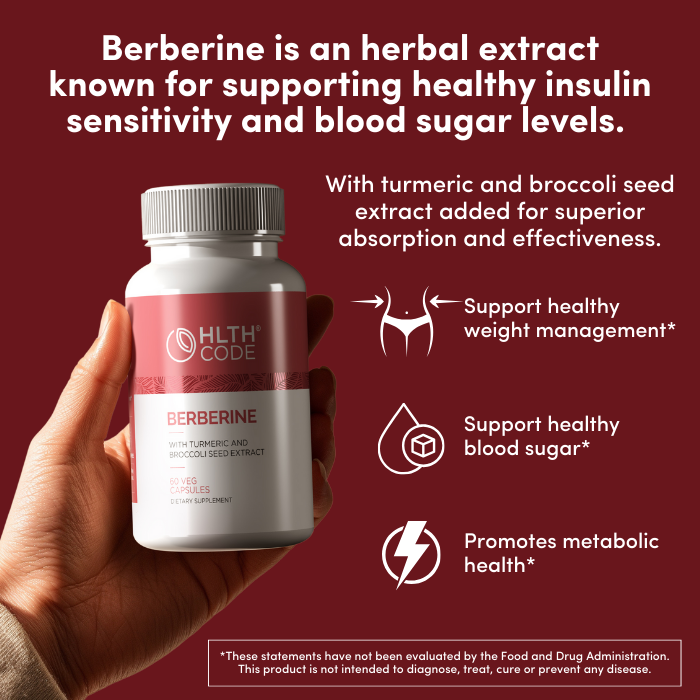

Insulin Resistance: The Hidden Driver of Heart Disease

Insulin resistance is a root cause of:

- High triglycerides

- Low HDL

- Abdominal obesity

- Hypertension

- Inflammation

This cluster of symptoms, known as metabolic syndrome, dramatically increases the risk of heart disease—even in people with “normal” LDL.

Low-carb diets directly target insulin resistance by:

- Lowering blood sugar and insulin levels

- Reducing visceral (belly) fat

- Improving lipid metabolism[12]

That’s why people with metabolic syndrome often see cardiovascular improvements far beyond what statins or low-fat diets can offer.

What About the LDL Increase on Keto?

Some individuals (especially lean, athletic men) experience increases in LDL-C on very low-carb, high-fat diets. This has sparked concern, but here’s what the science suggests:

- These individuals often see increased LDL particle size, not number[13]

- They also see dramatic improvements in triglycerides, HDL, insulin, and inflammation

- No studies to date have linked increased LDL-C from keto diets with increased cardiovascular events in otherwise healthy individuals

A growing movement of researchers argues that context matters:

“An elevated LDL-C is not inherently dangerous in the presence of low inflammation, low insulin, and a healthy metabolic profile.”

– Dr. Nadir Ali, Cardiologist

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores and carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) scans are more predictive tools for long-term risk.

Low-Carb vs. Statins?

Statins lower LDL-C, but do not improve metabolic health. In fact:

- Statins can increase blood sugar and insulin resistance[14]

- They have minimal effects on triglycerides and HDL

- They come with side effects (e.g., muscle pain, fatigue)

Low-carb diets, on the other hand:

- Reduce multiple cardiovascular risk factors simultaneously

- Improve blood pressure, insulin, inflammation, and body fat

- Are drug-free, dietary interventions

Some researchers now advocate low-carb diets as first-line therapy for metabolic syndrome and heart disease prevention[15].

Summary: Don’t Fear Fat—Fix the Metabolism

Low-carb and ketogenic diets:

- Lower triglycerides

- Raise HDL

- Improve LDL particle size

- Reduce inflammation

- Improve insulin resistance

- Support weight loss and visceral fat reduction

While LDL-C may rise in some, it is usually offset by improvements in other, more meaningful markers of cardiovascular risk.

The bottom line? Low-carb diets don’t damage your heart—they often protect it, especially if you’re insulin resistant, overweight, or metabolically unwell.

FAQs

- If my LDL goes up on keto, should I be worried?

Not necessarily. Look at the full picture: if your triglycerides drop, HDL rises, inflammation decreases, and you’re losing visceral fat, your heart risk may actually be going down. - Can low-carb diets help lower blood pressure?

Yes. Many studies show reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, often leading to reduced reliance on hypertension medications. - What about saturated fat? Doesn’t it clog arteries?

Modern research shows saturated fat does not directly cause heart disease. The link is weak and likely dependent on context (e.g., insulin resistance, refined carbs). Healthy fats from whole foods (eggs, meat, coconut oil, butter) are safe for most. - Should I still get a CAC scan or ApoB test?

Yes! If you’re concerned about cardiovascular risk, get a Coronary Artery Calcium score and consider testing ApoB and LDL particle number. These are more predictive than LDL-C alone. - Who should be cautious with high-fat diets?

People with rare genetic conditions like familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) or Lipoprotein(a) elevation should work with a lipidologist. But for most people, metabolic health is a better predictor of heart risk than cholesterol alone.

References

-

- Sniderman AD, Williams K, Contois JH, et al. “A Meta-Analysis of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol, Non–High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol, and Apolipoprotein B as Markers of Cardiovascular Risk.” JAMA. 2003;290(7):932–940.

- Krauss RM. “Lipoprotein subfractions and cardiovascular disease risk.” Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21(4):305–311.

- Volek JS, Phinney SD. “The art and science of low carbohydrate performance.” Beyond Obesity LLC; 2012.

- Tay J, Luscombe-Marsh ND, Thompson CH, et al. “Comparison of low- and high-carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes management: a randomized trial.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(4):780–790.

- da Luz PL, Favarato D, Faria-Neto JR Jr, Lemos P, Chagas ACP. “High ratio of triglycerides to HDL-cholesterol predicts extensive coronary disease.” Clinics. 2008;63(4):427–432.

- Libby P. “Inflammation in atherosclerosis.” Nature. 2002;420(6917):868–874.

- Forsythe CE, Phinney SD, Fernandez ML, et al. “Comparison of low fat and low carbohydrate diets on circulating fatty acid composition and markers of inflammation.” Lipids. 2008;43(1):65–77.

- Sharman MJ, Kraemer WJ, Love DM, et al. “A ketogenic diet favorably affects serum biomarkers for cardiovascular disease in normal-weight men.” J Nutr. 2002;132(7):1879–1885.

- Hallberg SJ, McKenzie AL, Williams PT, et al. “Effectiveness and safety of a novel care model for the management of type 2 diabetes at 2 years: an open-label, non-randomized, controlled study.” Front Endocrinol. 2018;9:1–11.

- Bueno NB, de Melo IS, de Oliveira SL, da Rocha Ataide T. “Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” Br J Nutr. 2013;110(7):1178–1187.

- Volek JS, Feinman RD. “Carbohydrate restriction improves the features of Metabolic Syndrome. Metabolic Syndrome may be defined by the response to carbohydrate restriction.” Nutr Metab (Lond). 2005;2:31.

- Ludwig DS, Willett WC, Volek JS, Neuhouser ML. “Dietary fat: From foe to friend?” Science. 2018;362(6416):764–770.

- Sharman MJ, Gomez AL, Kraemer WJ, Volek JS. “Very low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets affect fasting lipids and postprandial lipemia differently in overweight men.” J Nutr. 2004;134(4):880–885.

- Cederberg H, Stancáková A, Yaluri N, et al. “Increased risk of diabetes with statin treatment is associated with impaired insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion: a 6-year follow-up study of the METSIM cohort.” Diabetologia. 2015;58(5):1109–1117.

- Feinman RD, Pogozelski WK, Astrup A, et al. “Dietary carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in diabetes management: critical review and evidence base.” Nutrition. 2015;31(1):1–13.

This article is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment and should never be relied upon for specific medical advice.