Artificial Sweeteners and Insulin

The Not-so-sweet Insulin Effect of (Some!) Artificial Sweeteners

Sweeteners are a broad class of non-nutritive compounds—things that taste like sugar but provide little or no calories. The evidence on specific sweeteners and insulin is sparse, though there is enough to mention. There appears to be a connection, insofar as correlational studies find that people who drink an artificially sweetened (diet) soda daily have a 36% greater chance of developing the metabolic syndrome (remember that it used to be called “insulin resistance syndrome”) and a whopping 67% increased risk of type 2 diabetes [1]. How can this be when diet soda has no calories? Well, there’s no clear answer; just a few theories.

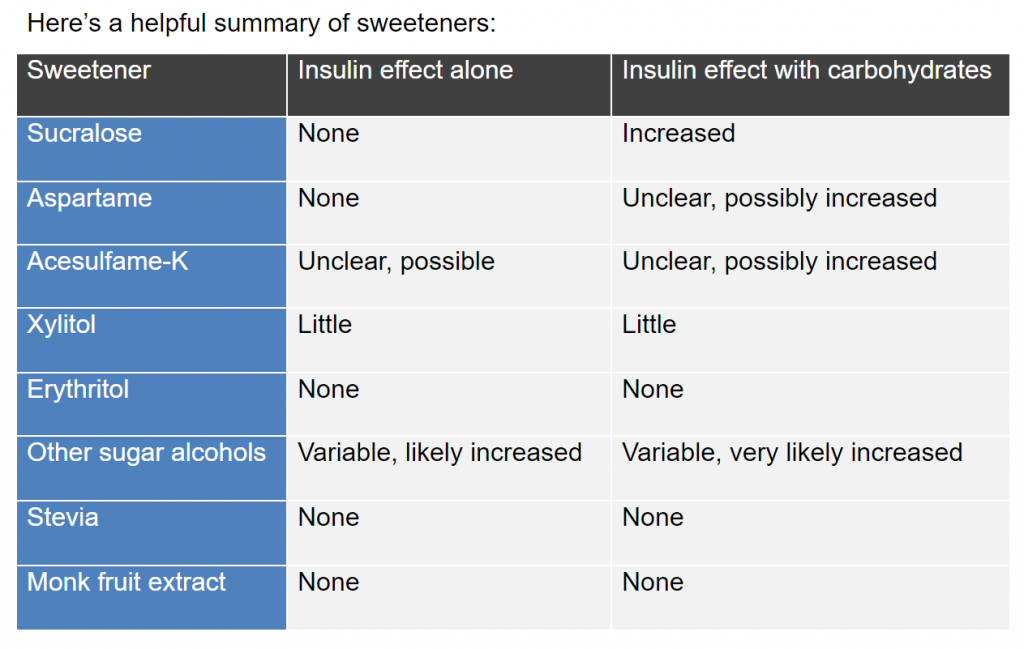

Before diving in, it’s important to emphasize that not all sweeteners are created equal; some are indeed “created”—made in a lab, while others are natural. This might explain why we see different effects with different sweeteners. Most of the research, including that cited below, is based on artificial sweeteners (e.g., aspartame, etc.) and sugar alcohols (e.g., maltitol, etc.). For the purposes of this article, I’ll focus on these two classes of sweeteners, artificial and sugar alcohol sweeteners, not natural sweeteners like stevia and monk fruit extract.

First, artificial sweeteners may make you want “real” food [2]. In other words, when your body tastes something sweet, it expects a corresponding load of energy—something, anything, that will fuel the body. However, when that energy doesn’t come (remember, the sweetener itself doesn’t provide anything real), the body craves something that will provide energy. Thus, the person starts out avoiding food by consuming the fake sweetener, then, in the end, ends up eating it anyway. This could be relevant for someone drinking a diet soda—sweet, but no calories. It’s likely less relevant if someone is eating something a food with a sweetener that also contains calories from other nutrients (i.e., protein and fat).

Second, artificial sweeteners make you think you can eat more [3]. In this case, a person purchases an item of food that is artificially sweetened and, in so doing, believes they can be more liberal with other foods. Thus, the person eats more than they otherwise would. For example, a person orders a diet soda to go with their fast-food lunch and because of the diet soda, the person thinks “I am gonna get a larger order of fries!”

Third, some artificial sweeteners do elicit an insulin response [4]. This phenomenon is known as the cephalic phase insulin response (CPIR) and we believe that it helps prepare the body for the inevitable carbohydrate load that comes with it. Because it should! In nature, anything sweet would be a carbohydrate. The CPIR is simply the body’s way of “priming the pump” by releasing a little insulin in anticipation of a carbohydrate load, which will cause a subsequent greater insulin release, whether consumed alone or with carbohydrates. This can include sucralose, xylitol, and most other sweeteners that end with “~ol”.

Take-away Thoughts

We all enjoy eating sweets, though we should exercise caution with artificial and sugar alcohol sweeteners, as they may negatively impact insulin levels, may prompt us to eat more unhealthy foods, or even cause gut issues. Thankfully, there are many good treats available that we can enjoy in moderation that are sweetened with natural, healthier sweeteners, such as monk fruit extract and stevia that have no effect on your insulin levels.

1. Nettleton JA, Lutsey PL, Wang Y, Lima JA, Michos ED, Jacobs DR, Jr.: Diet soda intake and risk of incident metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Diabetes care 2009, 32:688-694.

2. Blundell JE, Hill AJ: Paradoxical effects of an intense sweetener (aspartame) on appetite. Lancet 1986, 1:1092-1093.

3. Swithers SE, Davidson TL: A role for sweet taste: calorie predictive relations in energy regulation by rats. Behavioral neuroscience 2008, 122:161-173.

4. Tonosaki K, Hori Y, Shimizu Y, Tonosaki K: Relationships between insulin release and taste. Biomed Res 2007, 28:79-83.

5. Ferland A, Brassard P, Poirier P: Is aspartame really safer in reducing the risk of hypoglycemia during exercise in patients with type 2 diabetes? Diabetes care 2007, 30:e59.

6. Just T, Pau HW, Engel U, Hummel T: Cephalic phase insulin release in healthy humans after taste stimulation? Appetite 2008, 51:622-627.

7. Anton SD, Martin CK, Han H, Coulon S, Cefalu WT, Geiselman P, Williamson DA: Effects of stevia, aspartame, and sucrose on food intake, satiety, and postprandial glucose and insulin levels. Appetite 2010, 55:37-43.

This article is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment and should never be relied upon for specific medical advice.