How to enjoy potatoes or rice on a low carb diet

Some of the foods that low carb dieters miss the most are potatoes and rice. Both are staples in modern diets, but their high starch content wreaks havoc on the body’s glycemic response. Turnips and cauliflower are frequently used in place of potatoes or rice in low carb copycat recipes, and while this works for some people, others would rather avoid the substitutes altogether if it’s not the real thing.

If you’ve eaten a low carb diet for a while and are happy with your health and weight, you may have found that you can indulge in your favorite starchy foods occasionally without derailing your efforts. If you need to eat a ketogenic diet, control your insulin, or are looking to lose weight, however, eating such foods can pose more of a risk.

So is there a “safer” way to enjoy potatoes or rice on a low carb diet?

Resistant Starch

Starch can be classified into three types based on digestion rate: rapidly digestible starch (RDS), slowly digestible starch (SDS), and resistant starch (RS)[1]. Rapidly digestible starch is made of very long chains of glucose molecules bonded together and is what people typically mean when they think of high carb diets: cold cereal, crackers, pasta, rice, baked potatoes, and more. When these kinds of starches are eaten, they are readily absorbed by the small intestine and cause blood sugar to spike, thereby producing an insulinemic response. Some of the starch will be used as energy, while insulin will direct the excess to be stored as glycogen or as visceral fat.

Slowly digestible or slow-release starch takes longer for the body to break down, meaning that the impact on blood sugar and insulin is steadier and more moderate. These starches occur naturally in many fruits and vegetables, legumes, and grains. Because these foods take longer for the body to digest, they also increase satiety and reduce cravings.

Resistant starch does exactly what it sounds like: it resists digestion, functioning much like fiber. Once it reaches your large intestine, your healthy gut bacteria goes to work, fermenting the starch and producing butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid. Short-chain fatty acids are known to reduce inflammation and increase insulin sensitivity, making them a desirable part of any diet[2]. Other potential impacts of resistant starch include improved bowel and gut health, improved blood lipid profiles, thermogenesis, and more[3]. Foods naturally high in resistant starch include plantains, green bananas, raw oats, and raw potatoes.

While raw potatoes contain a good amount of resistant starch, they also contain the toxins solanine and lectins, which make eating raw potatoes dangerous. Heating potatoes destroys these compounds, but it also converts the resistant starch into rapidly digestible starch. But if raw potatoes should be avoided and cooked potatoes destroy the resistant starch, how do potatoes and other starchy foods fit into a low-carb diet?

Cooking and Cooling

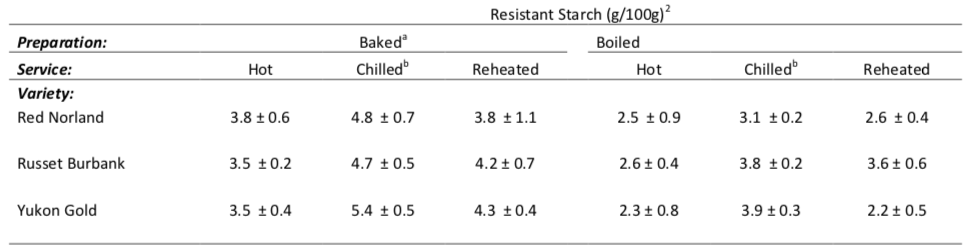

Fortunately, just as heat converts the resistant starch into RDS, cooling can actually convert much of the rapidly digestible starch back into resistant starch through a process called starch retrogradation. Researchers studying the impact of heating and cooling potatoes found that baked potatoes preserved more resistant starch than boiling them, but that cooling either form of potato significantly increased the amount of resistant starch[4,5]. Still another study shows almost triple the amount of resistant starch in potatoes cooked and cooled overnight[6]. Even when reheated, the resistant starch content remains higher than in potatoes cooked only once.

The best part is that this cooking-and-cooling process applies to other starches, like rice and pasta, with whole wheat varieties offering more benefits than bleached or white varieties[7].

So if you live a low-carb lifestyle but want to have your potatoes and eat them, too, just reach for the leftovers in your fridge.

References

- https://ift.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1750-3841.13809

- Sivaprakasam S, Prasad PD, Singh N. Benefits of short-chain fatty acids and their receptors in inflammation and carcinogenesis. Pharmacol Ther. 2016 Aug;164:144-51. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.04.007. Epub 2016 Apr 23. PMID: 27113407; PMCID: PMC4942363.

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1467-3010.2005.00481.x

- https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/560070

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0144861799001472

- Muir JG, O’Dea K. Measurement of resistant starch: factors affecting the amount of starch escaping digestion in vitro. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992 Jul;56(1):123-7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.1.123. PMID: 1609748.

- Hodges C, Archer F, Chowdhury M, Evans BL, Ghelani DJ, Mortoglou M, Guppy FM. Method of Food Preparation Influences Blood Glucose Response to a High-Carbohydrate Meal: A Randomised Cross-over Trial. Foods. 2019 Dec 25;9(1):23. doi: 10.3390/foods9010023. PMID: 31881647; PMCID: PMC7022949.

This article is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment and should never be relied upon for specific medical advice.