Debunking 10 Common Wellness Myths

In the era of information overload, it’s easy to fall victim to wellness myths that sound plausible but lack legitimate scientific backing. From diet fads to exercise trends, misconceptions about health and wellness abound. To help separate fact from fiction, let’s delve into ten common wellness myths and debunk them using scientific evidence.

Myth 1: Detox Diets Cleanse Your Body of Toxins

Detox diets often claim to rid the body of harmful toxins and promote weight loss. However, scientific research suggests otherwise. The human body has sophisticated mechanisms, primarily the liver and kidneys, for detoxification. Popular detox diets typically lack scientific evidence and may even be harmful, leading to nutrient deficiencies and disruptions in metabolism1.

Myth 2: You Need to Drink 8 Glasses of Water a Day

The recommendation to drink eight glasses of water per day is pervasive but lacks scientific support. While it’s a reasonable goal, the actual water needs vary depending on factors like age, weight, climate, and activity level. The Institute of Medicine suggests adequate daily intake is based on individual needs2, while the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine recommends that an appropriate daily intake of fluid is approximately 15.5 cups (3.7 liters) of fluids a day for men and 11.5 cups (2.7 liters) of fluids a day for women. Note that roughly 20% of daily fluid intake usually comes from food and the rest from water and other beverages.

Myth 3: Spot Reduction Exercises Target Fat Loss in Specific Areas

Many people believe that performing exercises targeting specific body parts will reduce fat in those areas. However, spot reduction is a myth. Fat loss occurs uniformly throughout the body in response to overall calorie expenditure. While targeted exercises can strengthen and tone specific muscles, they do not selectively burn fat in those areas3.

Myth 4: Eating Fat Makes You Fat

The notion that dietary fat directly translates to body fat is outdated and dangerous. Research indicates that the type and amount of fat consumed play a more significant role in health than simply avoiding fat altogether. Healthy fats from short-, medium- and long-chain sources are essential for proper bodily function and can aid in weight management4.

Myth 5: All Carbohydrates Are Bad for You

While there are no essential carbohydrates, some individuals take the anti-carb stance to an extreme. It’s the refined carbohydrates and added sugars that should be eliminated from the diet, not necessarily all carbs5. Prebiotic fiber, for instance, is technically a carbohydrate, but is utilized by beneficial gut bacteria for improved gut health and is not converted to glucose in the body.

Myth 6: Organic Foods Are Always Healthier

While organic farming practices may (but not always) offer benefits such as reduced pesticide exposure, organic foods are not inherently healthier than conventionally grown counterparts. Nutrient content will vary based on factors like soil quality, crop rotation and harvesting methods. Of more importance is prioritizing a diet that delivers complete macro- and micro-nutrients, whether organic or not6.

Myth 7: Stretching Prevents Injury and Improves Performance

While stretching can improve flexibility and range of motion, its role in injury prevention and performance enhancement is not as clear-cut as once thought. Dynamic warm-ups and targeted strength exercises may be more effective in preventing injury and improving athletic performance. Moreover, excessive static stretching before exercise may actually impair muscle function and performance7.

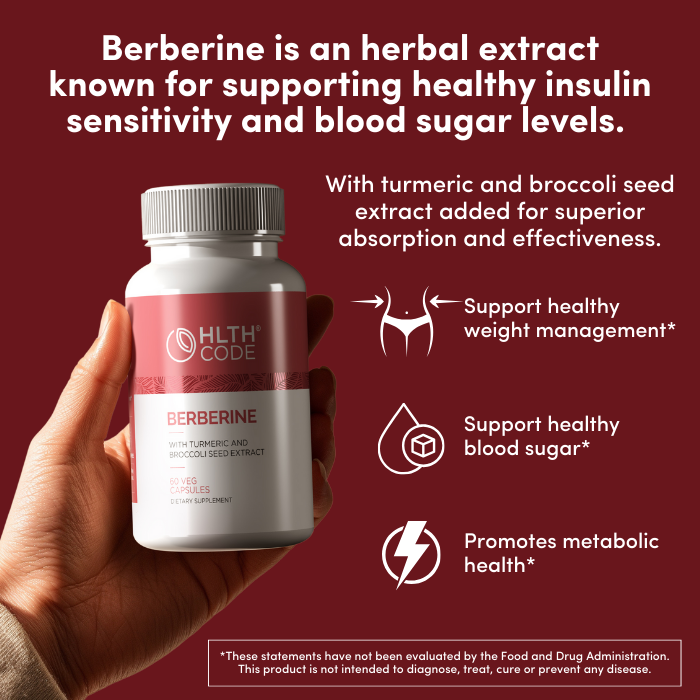

Myth 8: Supplements Can Replace a Balanced Diet

Supplements are aptly named, as they are a wonderful way to help contribute to (or supplement) a diet, but they shouldn’t be used as the sole source of micronutrients. A complete diet consisting of whole foods provide a complex matrix of nutrients and phytochemicals that supplements aren’t intended to fully replace8.

Myth 9: Sweat Is an Indicator of a Good Workout

The amount of sweat produced during exercise is not necessarily indicative of the effectiveness of the workout. Sweating is the body’s way of regulating temperature, and factors like environmental conditions and individual differences in sweat rate play a significant role. A productive workout should be judged based on factors like intensity, duration, and progression over time, rather than the amount of sweat produced9.

Myth 10: More Exercise Is Always Better

While regular physical activity is crucial for overall health and well-being, more exercise is not always better. Overtraining can lead to fatigue, injury, and burnout, ultimately hindering progress and enjoyment of physical activity. Rest and recovery are essential components of any exercise routine, allowing the body to repair and adapt to the stress of exercise10.

References

- Smith, M. J. (2017). Detox Diets: Cleansing the Body. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health (pp. 289-295). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-384947-2.00113-6

- Institute of Medicine. (2004). Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10925

- Vispute, S. S., Smith, J. D., LeCheminant, J. D., Hurley, K. S. (2011). The effect of abdominal exercise on abdominal fat. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(9), 2559-2564. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181fb4a46

- Mozaffarian, D., Hao, T., Rimm, E. B., Willett, W. C., Hu, F. B. (2011). Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. New England Journal of Medicine, 364(25), 2392-2404. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1014296

- Slavin, J. L. (2013). Carbohydrates, Dietary Fiber, and Resistant Starch in White Vegetables: Links to Health Outcomes. Advances in Nutrition, 4(3), 351S–355S. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.112.003159

- Dangour, A. D., Dodhia, S. K., Hayter, A., Allen, E., Lock, K., Uauy, R. (2009). Nutritional quality of organic foods: a systematic review. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 90(3), 680-685. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.28041

- Behm, D. G., Blazevich, A. J., Kay, A. D., McHugh, M. (2016). Acute effects of muscle stretching on physical performance, range of motion, and injury incidence in healthy active individuals: a systematic review. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 41(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0235

- Kantor, E. D., Rehm, C. D., Du, M., White, E., Giovannucci, E. L. (2016). Trends in Dietary Supplement Use Among US Adults From 1999-2012. JAMA, 316(14), 1464-1474. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.14403

- Cotter, J. D., Thornton, S. N., Lee, J. K. W., Laursen, P. B. (2014). Are we being drowned in hydration advice? Thirsty for more? Extreme Physiology & Medicine, 3(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-7648-3-18

- Halson, S. L. (2014). Sleep in elite athletes and nutritional interventions to enhance sleep. Sports Medicine, 44(Suppl 1), S13-S23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0147-0

This article is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment and should never be relied upon for specific medical advice.