Low-Fat Diets: More Harm Than Good?

Where it started

If you’ve ever tried to lose weight, there is a good chance that you’ve at least considered a low-fat diet. Going on a low-fat diet has ties back to the 1940’s, when there were some scientific studies published seemingly linking high-fat diets to high cholesterol. This made way for the thought that “going low-fat” could potentially lower the risk of heart disease. Even though some scientists and researchers were extremely skeptical of these findings, the low-fat diet began gaining significant ground in the medical community, media and politics (1).

In the 1960’s, America witnessed a huge shift. The low-fat diet, which was originally created to treat and prevent heart disease, became the leading nutrition advice in the nation. Popular magazines like Time and Prevention shared low-fat nutrition information as ways to promote heart health and weight reduction (1). In 1977, the US Dietary Guidelines were published and even without significant evidence from randomised controlled trials and testing, these guidelines recommended a significant reduction in dietary fat, and thus began the nationwide mentality to fear fat (2).

With the popularity surrounding low-fat diets, and an apparent host of corroborating research backing it, you would expect to see a massive change in a positive direction regarding the weight of American people, as well as a marked decrease in instances of chronic diseases such as heart failure and diabetes. Unfortunately, this just hasn’t been the case.

Weight Loss

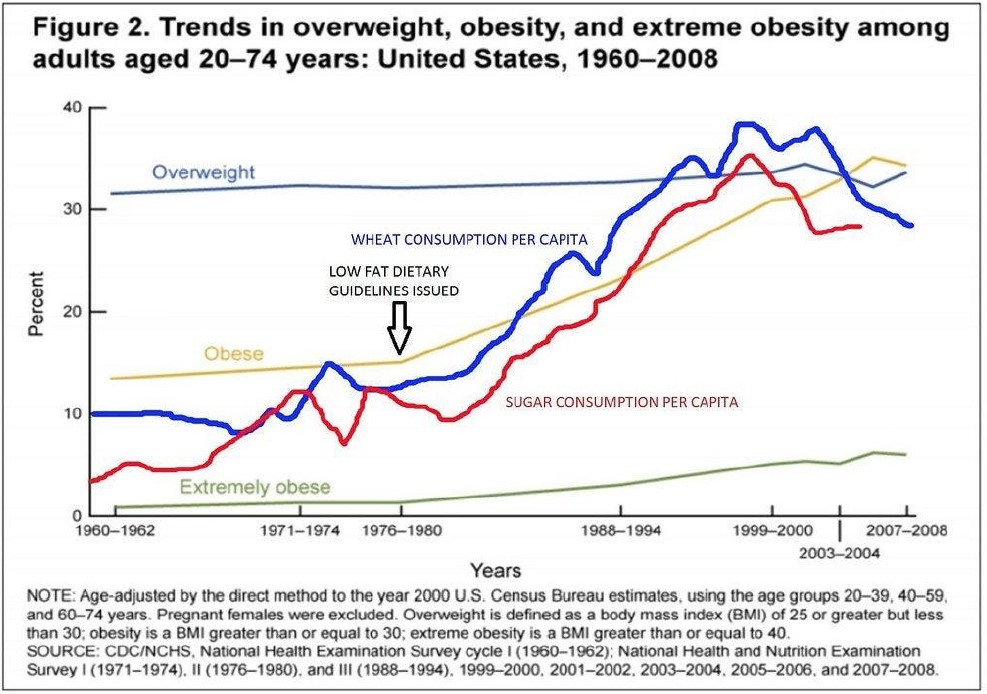

Low-fat diets were (and still are) often recommended for one to lose weight. The logic behind a low-fat diet is that 1 gram of fat equals 9 calories, whereas 1 g of protein and/or carbohydrate equals 4. Naturally, one would believe that cutting fat would inevitably lead to lower overall calorie consumption and in turn, to weight loss. Even if your provider or dietitian doesn’t directly say to follow a “low-fat” diet, you can see that many diets are based on this principle. Whether it’s points or red light foods, you can see that ostracized macronutrient is almost always fat! This assumes that the “calories in vs. calories out” method is without flaw – (see Dr. Bikman’s post on calories here). However, even with the huge push for everyone to eat low-fat, we continue to see the numbers for obesity rise. Even more interesting is that the date the low-fat guidelines were put into place marked the spike in the obesity epidemic (See Figure 2 above).

Fat is incredibly satiating. In a very interesting study done by Dr. Guenther Boden, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, 10 overweight adults were studied in a metabolic ward for almost a month. The first week they were allowed to eat from a buffet where everything they ate was weighed. For the latter duration of the study, the participants ate only low-carb, high-fat foods. On average, for the first week, the participants ate ~3100 calories daily, but for the last weeks of the study on high-fat, low-carb foods, they ate only ~2200 calories. They also reported a great level of fullness during the latter half which was the lower calorie intake (3). Another study found that a low-carbohydrate diet, consisting of more fat and protein, better preserved satiation than a low-fat diet (4). Lastly, The Women’s Health Initiative, which studied 50,000 women on low-fat diets found that they had no significant weight loss (Women’s Health Initiative (5). When the body is full, especially for longer periods of time, people tend to eat less, thus leading to weight loss. However, when you remove fat from the diet, you remove that satiating factor, encouraging more food consumption.

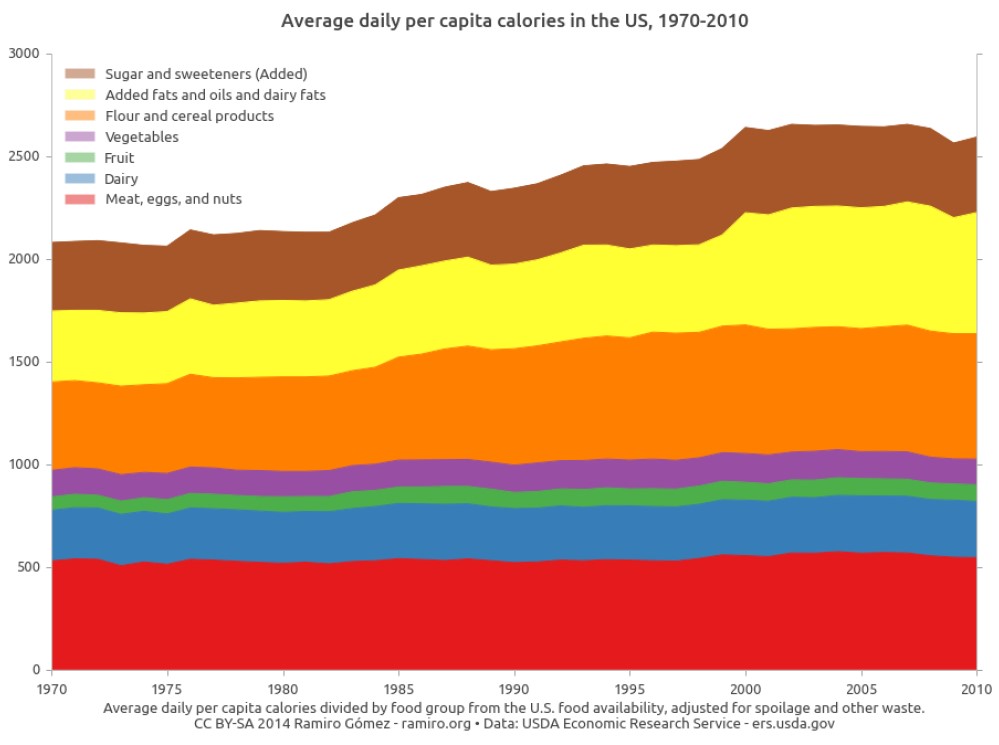

When people jumped on the low-fat craze, they started overconsuming carbs. Food corporations started pumping out low-, no-, or reduced-fat foods, most of which contained an alarming amount of sugar or other additives. As it turns out, when you remove fat, you typically have to add something like sugar, high fructose corn syrup, MSG, or salt to get the product to taste good enough to sell. Oftentimes these products were lower in fat, but contained the same amount of calories and a much higher amount of refined carbohydrates. So you can imagine the scenario this created– people went from eating satiating real food fats that help stabilize blood sugar, to a chemical storm of fake food riddled with additives and sugar. Take a quick look at the image above and you’ll see that calories from natural fat sources like meat, eggs and nuts have stayed relatively the same, but calories from processed carbohydrate sources like flours, cereal products, sugar and sweeteners have risen dramatically.

While the low-fat diet may still be prescribed in a lot of different settings, it may not be the most beneficial to your health. Don’t buy into fearing fat, it’s incredibly important for the body. This may be especially true if you suffer from any of the insulin resistant related conditions or conditions discussed above. It’s important to work with your health care provider before switching dietary patterns, and work with a professional who can help you reach your goals safely.

Temple Stewart is a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist specializing in low-carb/ketogenic diets. She graduated from the University of Tennessee before starting her career at the Veteran’s Affairs hospital in Bay Pines, Florida. She now operates a telehealth private practice focusing on health and weight loss. You can find her on Instagram @The.Ketogenic.Nutritionist.

References

1. La Berge, A. F. (2007). How the Ideology of Low Fat Conquered America. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 63(2), 139–177. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhmas/jrn001

2. Harcombe, Z., Baker, J. S., Cooper, S. M., Davies, B., Sculthorpe, N., DiNicolantonio, J. J., & Grace, F. (2015). Evidence from randomised controlled trials did not support the introduction of dietary fat guidelines in 1977 and 1983: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2014-000196

3. Boden, G., Sargrad, K., Homko, C., Mozzoli, M., & Stein, T. P. (2005). Effect of a Low-Carbohydrate Diet on Appetite, Blood Glucose Levels, and Insulin Resistance in Obese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Annals of Internal Medicine, 142(6), 403. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-142-6-200503150-00006

4. Hu, T., Yao, L., Reynolds, K., Niu, T., Li, S., Whelton, P., He, J., & Bazzano, L. (2016). The effects of a low-carbohydrate diet on appetite: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases, 26(6), 476–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2015.11.011

5. Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) – Full Text View. Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov. (n.d.). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00000611

This article is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment and should never be relied upon for specific medical advice.