The Silent Threat of Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress is a biological process that has garnered significant attention in recent years due to its implications in a wide range of diseases and aging processes. In this article, you’ll learn what oxidative stress is, the factors that contribute to it—particularly diet, early warning signs, and practical strategies to mitigate its impact.

What is Oxidative Stress?

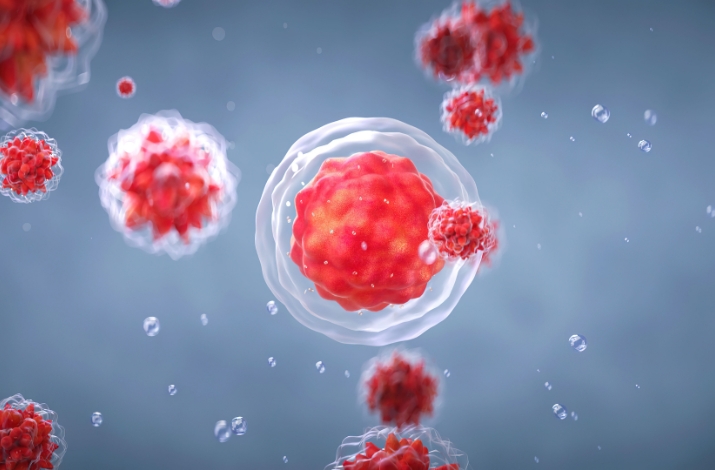

Oxidative stress occurs when there is an imbalance between the production of free radicals and the body’s ability to neutralize them with antioxidants. Free radicals, particularly reactive oxygen species (ROS), are unstable molecules that can cause cellular damage. Normally, the body maintains a balance between the generation of ROS and their elimination through antioxidant defenses. However, when this balance is disrupted, oxidative stress can occur, leading to cellular damage and contributing to the development of various chronic diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Factors Contributing to Oxidative Stress

- Diet and Nutritional Imbalances: The modern diet, rich in processed foods, refined sugars, and unhealthy fats like seed oils, is a significant contributor to oxidative stress. High intake of carbohydrates, particularly refined carbs, can lead to increased blood glucose levels, which in turn may increase the production of free radicals. Furthermore, diets low in antioxidants—beneficial compounds found in fruits, vegetables, and other whole foods—can weaken the body’s ability to combat oxidative stress.

- Environmental Toxins: Exposure to pollutants, such as heavy metals, pesticides, and tobacco smoke, can increase the production of free radicals. These environmental toxins disrupt cellular function and overwhelm the body’s antioxidant defenses.

- Physical Inactivity and Obesity: Sedentary lifestyles and obesity are closely linked to oxidative stress. Excess adipose tissue, especially visceral fat, is metabolically active and can generate free radicals, exacerbating oxidative stress.

- Chronic Stress: Psychological stress can trigger the production of stress hormones like cortisol, which can lead to increased free radical production. Chronic stress also impairs the immune system and reduces antioxidant defenses.

- Aging: As we age, the body’s natural antioxidant defenses weaken, making it more susceptible to oxidative damage. This contributes to the aging process and the development of age-related diseases.

Early Warning Signs of Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress may manifest in various ways, and recognizing these early signs can be crucial for preventing long-term damage:

- Fatigue: Persistent tiredness or a feeling of low energy can be an early indicator of oxidative stress, as cellular damage disrupts normal energy production.

- Memory and Cognitive Decline: Difficulty concentrating, forgetfulness, or cognitive decline can result from oxidative damage to brain cells.

- Skin Aging: Premature wrinkles, fine lines, and age spots may be signs of oxidative stress affecting skin cells.

- Frequent Infections: A weakened immune system, resulting in frequent colds or infections, may suggest oxidative stress.

- Muscle and Joint Pain: Unexplained muscle soreness or joint pain could indicate oxidative damage to tissues.

Strategies to Reduce Oxidative Stress

Given the potential health risks associated with oxidative stress, implementing strategies to reduce its impact is essential. Here are the top ten most effective approaches:

- Adopt a Low-Carb Diet: Diet plays a pivotal role in managing oxidative stress. A low-carb or ketogenic diet, which reduces carbohydrate intake and increases healthy fats, can help stabilize blood glucose levels and reduce the production of free radicals. Ketogenic diets, in particular, have been shown to enhance mitochondrial function and reduce oxidative stress markers1. Additionally, low-carb diets often result in weight loss, further decreasing oxidative stress associated with obesity.

- Increase Antioxidant Intake: Consuming foods rich in antioxidants can help neutralize free radicals. Antioxidants like vitamins C and E, selenium, and flavonoids are abundant in fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds. Prioritize berries, leafy greens, and cruciferous vegetables, as they are particularly high in antioxidants2.

- Exercise Regularly: Regular physical activity has been shown to enhance the body’s antioxidant defenses and reduce oxidative stress3. Moderate exercise, such as walking, swimming, or yoga, can improve circulation, reduce inflammation, and boost overall health.

- Manage Stress: Chronic psychological stress is a significant contributor to oxidative stress. Techniques such as meditation, deep breathing exercises, religious observation, and mindfulness can reduce stress levels and improve antioxidant capacity4. Adequate sleep is also crucial, as it allows the body to repair and regenerate, reducing oxidative damage.

- Avoid Environmental Toxins: Reducing exposure to environmental pollutants can significantly decrease oxidative stress. Avoid tobacco smoke and reduce exposure to industrial chemicals, including pesticides5.

- Supplement Wisely: Certain supplements can enhance the body’s antioxidant defenses. For example, omega-3 fatty acids, coenzyme Q10, and alpha-lipoic acid have been shown to reduce oxidative stress6. However, supplementation should be approached cautiously and under the guidance of a healthcare provider to avoid potential adverse effects.

- Optimize Mitochondrial Function: Mitochondria are the powerhouses of the cell, and their dysfunction is a significant source of oxidative stress. Supporting mitochondrial health through diet, exercise, and supplements like magnesium and acetyl-L-carnitine can reduce oxidative stress and improve energy levels7.

- Hydration: Proper hydration is essential for maintaining cellular health and reducing oxidative stress. Water helps flush out toxins and supports the body’s natural detoxification processes. Aim to drink enough water throughout the day.

- Maintain a Healthy Weight: Achieving and maintaining a healthy weight through diet and exercise can reduce the oxidative stress associated with obesity. This involves not just fat loss but also maintaining lean muscle mass, which can improve metabolic health and reduce inflammation8.

- Support Gut Health: The gut microbiome plays a crucial role in regulating oxidative stress. Consuming probiotics, prebiotics, and a diet rich in fiber can support a healthy gut flora, reducing inflammation and oxidative stress9.

Conclusion

Oxidative stress is a complex and multifaceted condition with significant implications for health and disease. It is influenced by various factors, including diet, environmental toxins, physical inactivity, chronic stress, and aging. Recognizing the early warning signs of oxidative stress is crucial for taking proactive steps to mitigate its impact.

References

- Paoli, A., Rubini, A., Volek, J. S., & Grimaldi, K. A. (2013). Beyond weight loss: a review of the therapeutic uses of very-low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diets. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 67(8), 789-796. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2013.116

- Carlsen, M. H., Halvorsen, B. L., Holte, K., Bøhn, S. K., Dragland, S., Sampson, L., … & Blomhoff, R. (2010). The total antioxidant content of more than 3100 foods, beverages, spices, herbs, and supplements used worldwide. Nutrition Journal, 9(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-9-3

- Powers, S. K., & Jackson, M. J. (2008). Exercise-induced oxidative stress: cellular mechanisms and impact on muscle force production. Physiological Reviews, 88(4), 1243-1276. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00031.2007

- Juster, R. P., McEwen, B. S., & Lupien, S. J. (2010). Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(1), 2-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002

- Valko, M., Rhodes, C. J., Moncol, J., Izakovic, M., & Mazur, M. (2006). Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chemico-biological Interactions, 160(1), 1-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2005.12.009

- Bentinger, M., Tekle, M., & Dallner, G. (2010). Coenzyme Q–biosynthesis and functions. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 396(1), 74-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.147

- Choi, S. W., & Friso, S. (2010). Epigenetics: A New Bridge between Nutrition and Health. Advances in Nutrition, 1(1), 8-16. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.110.1004

- Frühbeck, G., Gómez-Ambrosi, J., Muruzábal, F. J., & Burrell, M. A. (2001). The adipocyte: a model for integration of endocrine and metabolic signaling in energy metabolism regulation. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 280(6), E827-E847. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.6.E827

- Bischoff, S. C. (2011). ‘Gut health’: a new objective in medicine? BMC Medicine, 9(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-24

This article is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment and should never be relied upon for specific medical advice.