How the Food Pyramid Impacted American Health

For decades, the food pyramid has been a ubiquitous symbol in nutritional education, shaping dietary recommendations worldwide. Developed by health authorities to guide individuals toward a balanced and healthy diet, the pyramid has been a cornerstone of nutritional guidance. However, as greater scientific understanding of nutrition has advanced, criticisms have emerged regarding the accuracy and potential harm associated with the food pyramid.

The Origins of the Food Pyramid

The concept of a food pyramid originated in the 1960s as a response to increasing rates of heart disease and other diet-related health issues. The pyramid categorized food into five main groups and provided recommended serving sizes for each group. The base of the pyramid consisted of grains, followed by fruits and vegetables, then dairy and protein, with fats and sweets at the top. The intention was to emphasize the importance of a diet rich in grains, fruits, and vegetables while moderating intake of protein and especially fats.

The Impact on Weight

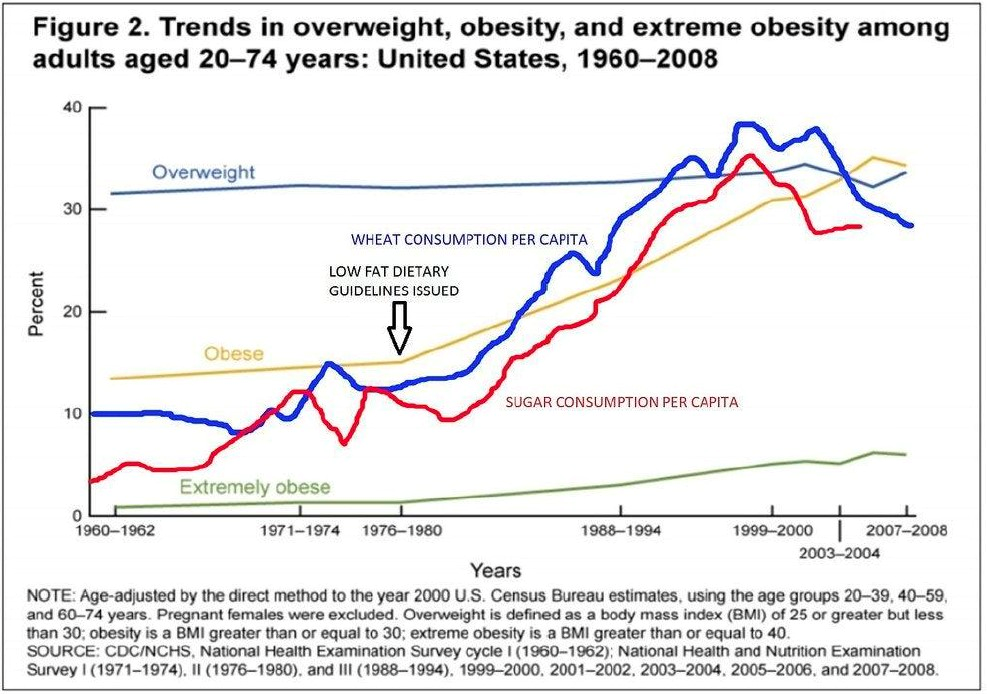

From the time that the US government first set dietary guidelines in 1977, the food industry has shifted the types of foods produced to the overall detriment of the public. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the average adult today weighs nearly 30 pounds more than an average adult in the late 1970’s.[1] The CDC’s own chart is illustrative:

Carbohydrate-centric Focus

One of the fundamental flaws of the food pyramid lies in its disproportionate emphasis on grains, particularly refined grains. The base of the pyramid encourages a significant portion of the diet to be comprised of refined carbohydrates, mainly in the form of bread, rice, and pasta.

Scientific studies have shown that diets rich in refined carbohydrates can lead to rapid spikes in blood sugar levels, causing insulin to be released in large quantities. Over time, this can contribute to the development of insulin resistance, a condition where cells become less responsive to insulin, ultimately leading to metabolic dysfunction and other health issues. A study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition highlighted the adverse effects of high glycemic index diets, which are often associated with excessive grain consumption, on insulin sensitivity and body weight.[2]

Minimizing Protein

The food pyramid recommended limited amounts of protein. Protein is required for the building, repair, and maintenance of muscles. It provides the necessary amino acids that the body uses to synthesize proteins, supporting muscle health and function.

Further, protein helps increase feelings of fullness and satiety, which can contribute to reduced overall calorie intake. Including protein in your diet can be beneficial for weight management and fat loss. Plus, a protein-rich diet is also known to improve body composition[3], help regulate blood glucose, boost metabolism, support immune and bone health, and much more.

While protein should be the “star” of any plate, the food pyramid put it far down the list.

Neglecting Healthy Fats

Another significant flaw in the food pyramid is its placement of fats and oils at the top, suggesting that they should be consumed sparingly. While it is essential to limit the intake of highly processed seed oils, the pyramid fails to distinguish between healthy fats and unhealthy fats present in processed and fried foods.

Recent research has demonstrated the importance of incorporating healthy fats into the diet for optimal health. For example, a systematic review and meta-analysis published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology concluded that higher consumption of unsaturated fats, particularly polyunsaturated fats and monounsaturated fats, is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease.[4] The food pyramid’s generalization regarding fat consumption undoubtedly contributes to a misunderstanding of the role fats play in a balanced and nutritious diet.

Influence of Industry Interests

Critics argue that the development and perpetuation of the food pyramid have been influenced by industry interests, particularly those of certain segments of the agricultural and food processing sectors. The prominence of refined grains in hyper-processed foods, for example, aligns with the economic interests of these industries, which clearly prioritize profit over public health.

A study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, discussed the influence of industry on dietary recommendations, emphasizing the conflicts of interest that may arise when organizations responsible for public health guidelines receive funding or support from industries that produce and promote certain foods.[5] Such conflicts of interest can potentially compromise the integrity of nutritional guidance, leading to recommendations that prioritize economic interests over the wellbeing of the American public.

Health Implications of the Food Pyramid

Rising Obesity Rates:

The food pyramid’s emphasis on a high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet has been criticized for contributing to the obesity epidemic. The focus on grains as a dietary staple may lead individuals to consume excess refined carbohydrates, which can contribute to weight gain and metabolic disorders.[6]

Cardiovascular Health Concerns:

The food pyramid’s recommendation to limit dietary fat, particularly saturated fat, has been questioned in light of recent research suggesting that not all fats pose a health risk. The avoidance of healthy fats, may lead to an imbalance in essential fatty acids, potentially impacting cardiovascular health.[7]

Blood Glucose Regulation:

The carbohydrate-centric focus of the food pyramid may contribute to issues related to blood glucose regulation. High intake of refined carbohydrates can lead to spikes and crashes in blood glucose levels, potentially increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes and metabolic disorders.[8]

Conclusion

The food pyramid, once considered a guiding light for dietary choices, is increasingly under scrutiny for its potential to mislead and to harm health. The disproportionate emphasis on grains, the limits on protein and fat consumption, and other limitations contribute to a flawed nutritional framework.

What to do? A growing body of clinical evidence shows that a diet that keeps blood glucose and insulin low by restricting carbohydrates yet is high in protein and healthy fats leads to superior health outcomes.[9]

References

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_adult_09_10/obesity_adult_09_10.htm

- Ludwig DS, Hu FB, Tappy L, Brand-Miller J. Dietary carbohydrates: role of quality and quantity in chronic disease. BMJ. 2018;361:k2340.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7539343/

- Astrup A., Magkos F, Bier DM, et al. Saturated Fats and Health: A Reassessment and Proposal for Food-Based Recommendations. JACC. 2020; 76 (7) 844–857.

- Nestle M. Food politics: How the food industry influences nutrition and health. University of California Press; 2013.

- Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2392-2404.

- de Souza RJ, Mente A, Maroleanu A, et al. Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h3978.

- Hu T, Mills KT, Yao L, et al. Effects of low-carbohydrate diets versus low-fat diets on metabolic risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(suppl_7):S44-S54.

- Walton, C. M., Perry, K., Hart, R. H., Berry, S. L. and Bikman, B. T. (2019) Improvement in Glycemic and Lipid Profiles in Type 2 Diabetics with a 90-Day Ketogenic Diet. J Diabetes Res. 2019, 8681959

This article is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not, nor is it intended to be substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment and should never be relied upon for specific medical advice.